Dr Dagmar Berne – pioneer of Australian women doctors

Portrait of Dr Dagmar Berne from the Univeristy of Sydney archives. Source: Neve, Marjorie Hutton (1980) ‘This Mad Folly!’ The History of Australia’s Pioneer Women Doctors Library of Australian History: North Sydney page 81

There are many people in the history of Australia who deserve greater recognition than they receive. And HistoryParkes would like to redress this injustice, primarily of those people who were one time residents of the Parkes Shire. One lady who deserves greater appreciation is Dr Dagmar Berne. Amongst the pioneers of Australian female medical practitioners, she is one of the “unhonoured and unsung” according to historian and author M.H. Neve (p. 10). The one time doctor of Trundle – the town she called home and where she passed away – was also the first woman to enrol in medicine in any Australian university. Dagmar Berne enrolled in medicine at University of Sydney in 1895. To fully understand why this is so significant, one needs to realise what life was like in late 1800s Australia.

The Victorian Era’s Attitude to Women – including Royal Opposition

To modern readers the idea of a female doctor may not seem anything out of the ordinary. However the prevailing viewpoint prior to Dagmar Berne’s enrolment was that while some careers were acceptable for women, medicine was not one of them. Indeed the thought of women pursuing a career was strongly opposed by the leading monarch of the day. Queen Victoria was quoted in 1870 as saying:

…The mad, wicked folly of woman’s rights…. Woman will become the most hateful, heartless and disgusting of human beings were she allowed to unsex herself… Let woman be what God intended; a helpmate for a man – but with totally different duties and vocations….

Neve (1980) (page 11)

Were Queen Elizabeth II to make such a statement today, it may be easily dismissed and the monarch open to criticism. However Queen Victoria had restored respectability to the monarchy and it is stated that “…when she celebrated her Diamond Jubilee the public outpouring of respect and devotion was immense to an unprecedented degree.” (Source: http://madmonarchist.blogspot.com.au/2013/04/monarch-profile-queen-victoria-of-great.html) Hence when Queen Victoria made a statement, it was adhered to and respected almost without question. M.H. Neve (1980) comments that British Prime Minister of the time, William Gladstone, initially recommended the inclusion of a ‘women’s clause’ in a new Charter for London University in 1861. Neve states that Gladstone was left under no illusions as to the ruling monarch’s opinions on the matter, and quietly withdrew his support for the Women’s Movement (page 20)

Indeed Queen Victoria is quoted in Neve’s book This Mad Folly: The History of Australia’s Pioneer Women Doctors from a letter Gladstone received:

‘…the circumstance respecting the Bill to give women the same position as men with regard to Parliamentary Franchise gives her an opportunity to observe that she had for some time past wished to call Mr Gladstone’s attention to the mad and utterly demoralising movement of the proposal to place women in the same position as to professions – as men; – and amongst others, in the Medical Line…. She is most anxious that it should be known that she not only disapproves but abhors the attempts to destroy all propriety and womanly feelings which would be inevitably be the result of what has been proposed…. but to tear away all barriers which surround a woman, and to propose that they should study with men – things which should not be named before them – certainly not in a mixed audience – would be to introduce a total disregard of that which must be considered as belonging to the rules and principles of morality.’

Neve (1980) page 20-21 (emphasis added by author)

Queen Victoria viewed women pursuing manly endeavours – such as medicine – as mad folly. Image Princess Beatrice of Battenberg; Queen Victoria by Unknown artist oil on canvas, late 1860s-early 1870s NPG 5828 © National Portrait Gallery, London used under permission of Creative Commons

However while Queen Victoria expressed her views, she was by no means the only obstacle to Dagmar Berne and her peers gaining enrollment at universities. The academic world, particularly those who wielded power to accept enrollment and determine whether students would graduate or not, held even stricter views than Queen Victoria’s. The University of Sydney only established a Faculty of Medicine on 13 June 1856, however it was an examining body and there was no teaching there for twenty-seven years (Moorhead, citing John Atherton Young and Nina Webb, “Prologue: The Foundation of the Faculty,” in Centenary Book of the University of Sydney Faculty of Medicine, edited by John Atherton Young, Ann Jervie Sefton, and Nina Webb; page 6). While Queen Victoria may have opposed women pursuing medicine, she was indirectly involved in the medical school taking up its teaching duties. As Moorhead (2008) records:

A British Empire incident eventually pulled the medical school out of its doldrums. In 1868 the visiting twenty-three year old son of Queen Victoria was shot at point blank range by a deranged Sydney Irish-Australian. This happened during a fundraising event full of local dignitaries. Immediately before the assassination attempt the prince had been chatting to the chancellor of Sydney University, Sir William Manning. The assassin also tried to shoot the chancellor bu missed. Prince Alfred survived and the local community as a thanks offering, and with the wish to dissociate itself from the Irish cause, raised funds which together with a generous bequest enabled the medical school as we know it to open in 1883 with a young Lowland Scottish professor, Anderson Stuart as dean and six male students. (page 6)

Dagmar Berne circa 1890. The photograph is by Fay’s Studios and contributed by State Records NSW. Source: Dictionary of Sydney website

The Scottish influence was strong on the University of Sydney’s new faculty, so much so that they were referred to as “men from the north of the Tweed” (Woodhouse citing Keith Inglis, “Centenary of the University of Sydney”, British Medical Journal no2 (1952): 439-441)

Dr Anderson Stuart was a graduate from Edinburgh University, which “…had a poor record of encouraging women to enter [university]” (R. Moorhead 2008 page 7) Moreover Moorhead (2008) states that “In 1870 there had been riots in the Edinburgh Surgeon’s Hall by male students wishing to stop women attending an anatomy exam (as extramural students)” (page 7). This was the institution that Dr Anderson Stuart graduated from, so it should not be a surprise that he held strong views on the subject of women studying medicine. While not implication Dr Anderson Stuart in the following, Moorhead (2008) refers to an article by Margaret Ross which states:

At the time of the riot, ‘one student seeing [the women’s] predicament rushed out and managed to get the gates open and escorted them inside, where they sat the exam in spite of the continuing noise inside and the forcible intrusion of poor bewildered sheep, which were pushed in by rioters. (page 7)

While the male students may have resorted to unusual methods to display the opposition to women students, the institutional elders were more pragmatic in their narrow-mindedness, as detailed by Moorhead (2008):

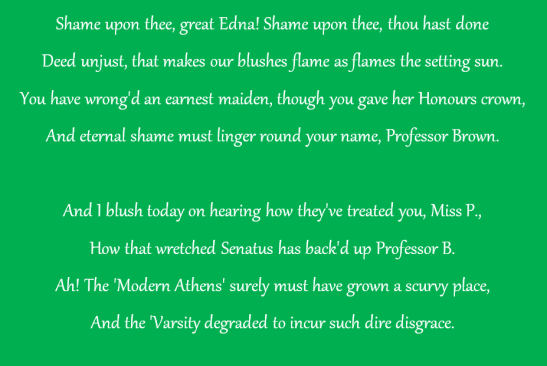

In the year that Anderson Stuart commenced undergraduate training in Edinburgh an extramural woman student came first in Chemistry and was eligible for a 200 pounds medal and a scholarship. This was blocked by Professor Crum Brown and with the Senate’s backing the next student, a male, became the recipient. (page 7)

This poem was published in protest to Edinburgh University’s decision to back Professor Crum Brown’s decision to deny the student who achieved first place in Chemistry the 200 pounds medal and scholarship they deserved. First place went to woman extramural student, so Professor Brown gave the medal and scholarship to the next student, a male. This was the culture in which Dagmar Berne attempted to graduate in medicine. Source: Ross, M. (1996). “The Royal Medical Society and Medical Women”. Proceedings of the Royal College of Physicians Edinburgh,26, 630. doi:10.2307/40111301 referenced in Moorhead, R. (2008). “Breaking New Ground: The Story of Dagmar Berne” Health and History,10(2), 4-22. doi:10.2307/40111301 Retrieved January 17, 2017, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40111301

With this viewpoint supported by his fellow students and those responsible for educating them, it is no wonder that Dr Anderson Stuart made the following statement, as referred by Neve (1980):

“I think that the proper place for women is in the home, and the proper function for a woman is to be a man’s wife, and for women to be the mothers of our future generations.”

Dr Anderson Stuart, Dean of the Faculty of Medicine, University of Sydney quoted in Neve (1980) page 11

While the dean’s comments were made in 1881, seven years before women were finally admitted as undergraduates, it would not be the last time that Dagmar Berne would encounter the powerful academic.

Whether male or female, a person choosing to go into the medical profession was doing it for passion, not the promise of fortune. Susanna De Vries (2001) describes the status quo for doctors:

All doctors before World War I worked eighteen to twenty-hour shifts, day in, day out. All hospital residents, male and female, were paid a pittance and regarded as being lucky to be there at all as the only entry into medicine lay through getting good references from their consultants. Female residents were paid even less than their male counterparts although women doctors worked hour for hour with their male colleagues and were ‘on call’ virtually round the clock. (page 95)

The Berne Family

Dagmar Berne was the daughter of parents Frederick Scoffwood Berne and Georgina Kenyon (née Witton). She was born November 16, 1866 (Witton (2008) page 30) Her father was Danish and emigrated to Australia, settling at Bega on the south coast of New South Wales. Her mother was born in Hobart and moved to Bega to join her brother in 1864. Historian Marjorie Hutton Neve describes Dagmar’s family:

Her father, Frederick Scoffwood Berne, was a Dane of good stock who, giving up his profession of jeweller, had migrated to Australia about the middle of last century, settling at Bega on the South Coast of New South Wales and taking up land. He married a Tasmanian widow with four children, and also begot four of his own – Georgina Dagmar, Florence, Eugenie and Frederick. He treated his stepchildren with the same solicitude and affection that he gave his own, and it was not until some years after his death that they knew their correct paternity. (Neve 1980 page 62)

She was rarely called Georgina – to everyone she was Dagmar – but she was described as “very delicate as a small child and as a baby was kept alive mainly on peach juice” (Neve, 1980 page 62). Perhaps because of her health, this was a reason for Dagmar pursuing a medical career. Neve states that “….she never became robust, and in maturity suffered from recurring bouts of pleurisy, which later developed into the tuberculosis that caused her early death (Neve, 1980 page 62).

![Map of Bernefield Estate at the time Georgina Berne was auctioning it. Dagmar's mother honoured her marriage to Frederick Berne by naming the streets of the estate 'Berne', 'Dagmar', 'Georgina' and 'Bega'. Today these streets are the site for a container terminal alongside the Princes Highway in St Peters. Source: The Bernefield Estate, St. Peters [cartographic material] : for auction sale on the ground, at 3 o'clock, Saturday 2nd November 1895 / Hardie & Gorman, auctioneers accessed on http://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/4513044](https://historyparkes.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/bernefield-estate.png?w=547)

Map of Bernefield Estate at the time Georgina Berne was auctioning it. Dagmar’s mother honoured her marriage to Frederick Berne by naming the streets of the estate ‘Berne’, ‘Dagmar’, ‘Georgina’ and ‘Bega’. Today these streets are the site for a container terminal alongside the Princes Highway in St Peters. Source: The Bernefield Estate, St. Peters [cartographic material] : for auction sale on the ground, at 3 o’clock, Saturday 2nd November 1895 / Hardie & Gorman, auctioneers accessed on http://catalogue.nla.gov.au/Record/4513044

…a prominent and ambitious local citizen. He was involved in public meetings, penned letters in The Bega Gazette, and lectured during his presidency of The Bega School of Arts, indicating a broad knowledge and interest in world affairs and scientific subjects.

Witton, V. (2014) Dagmar Berne Retrieved from http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/berne_dagmar

While all available sources indicate that Dagmar grew up in a loving and modernist home, tragedy was to strike when Dagmar was nine years old. The Bega Valley was in flood and Frederick Berne was out riding his horse to conduct some business. Reports vary as to the exact circumstances, however the only indisputable fact was that Frederick Berne drowned in the floodwaters. Great great great great niece, Dr Vanessa Witton, claims that after conducting some business he died while attempting to ride across a body of water (Witton, V. (2014) Dagmar Berne Retrieved from http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/berne_dagmar) In contrast, historian M. H. Neve claims that Mr Berne died while attempting to assist some fishermen (Neve (1980) page 62)

Tragedy strikes the Berne family, with Dagmar’s father drowning while out horse-riding. Source: DEATH OF MR. BERNE. (1874, April 2). The Bega Gazette and Eden District or Southern Coast Advertiser (NSW : 1865 – 1899), p. 2. Retrieved January 20, 2017, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article106753937

Whatever the truth of Frederick Berne’s fate, Dagmar’s mother was the sole parent for a second time, now with eight children. The family left the South Coast, moving to Sydney. The Bernes resided briefly at Mosman, then Darlington before calling the Cook’s River district home. The family home, Bernefield, was in the location of present-day St Peters. (Neve (1980) page 62). Witton (2014) states that Georgina Berne “… honoured her marriage with Frederick by calling the streets of the ‘Bernefield Estate’ Bega, Georgina, Berne, and Dagmar.” Due to building work on the Princes Highway all these streets have been consumed into a container terminal.

Berne Street is still listed on Google Maps. However it is where the container terminal is situated, the main road in foreground is Princes Highway, St Peters. Source: Google Street View of Berne Street in May 2016, retrieved from https://www.instantstreetview.com/@-33.916113,151.173419,139.1h,1.36p,0.27z January 20th, 2017

Dagmar’s Education & Enrollment

While Georgina Berne was the sole parent of eight children she was eager to continue the children’s education. Neve (1980) elaborates:

All the children attended Newtown Primary School for some years; but when Mrs Berne decided to send the girls in turn to a good school, she selected one where the food was healthy and the children well care for. This was Springfield Ladies’ College in Springfield Avenue, Darlinghurst, under the direction of Madame de Monsigny, which, being considered very elite, was expensive. As Dagmar was a boarder, her small sister (Mrs E.N. Buswell) on visiting there with her mother, was fascinated by the massive and exquisitely wrought-iron gates of the College and by the lovely garden stretching some distance down from Macleay Street over towards Victoria Street. (page 62)

Dagmar’s mind had been opened to the scientific world by her late father, who encouraged the asking of questions. Witton (2008) writes that

The girls were taught French and other ‘accomplishments’ considered suitable to the education of young ladies in the late nineteenth century. Visiting gentlemen lecturers taught Latin and Mathematics. Chemistry, Physics and Greek were offered to boys at neighbouring schools but were not taught at girls’ schools at the time. Dagmar was unhappy during the one term she spent at Springfield, and believed that the fees that her mother was paying were too high for the amount of useful learning she was receiving.

Retrieved from http://sydney.edu.au/arms/archives/history/documents/Dagmar.pdf on December 22, 2016

Neve (1980) may disagree with Dagmar’s distant relative about the length of time spent at the exclusive Springfield Ladies’ College but both historians agree that Dagmar’s time was an unhappy one, with Neve (1980) commenting:

She did not relish the social atmosphere of the College, preferring instead to give up her time to serious study rather than to be ‘finished’ as a young lady who would then make her debut in the social marriage market. She returned home and, having decided she would go to the University, then having recently opened its doors to women, it was arranged that she be privately coached for matriculation. Chemistry was taken at University, and Dagmar rode over daily from ‘Bernefield’ on horseback.

(page 62-63)

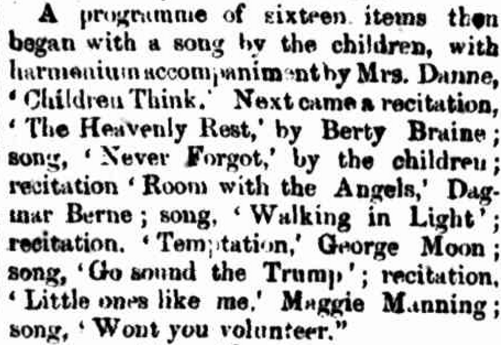

While Dagmar was described as shy, she still took part in public speaking. The article in the local newspaper lists a recitation by Dagmar Berne at a performance by the Children of the Wesleyan Sunday School. Source: ENTERTAINMENT. (1874, September 24). The Bega Gazette and Eden District or Southern Coast Advertiser (NSW : 1865 – 1899), p. 2. Retrieved January 20, 2017, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article106754814

Neve (1980) mentions that after taking the university examinations, Dagmar despaired convinced she would not pass. Dagmar made plans to assist her then sixteen year old sister, Florence, to open a small private school in the suburb of Tempe (page 63) So convinced was Dagmar in her inability to pass that a location was obtained, the students’ parents contaced and material purchased. A few days before the Berne sisters’ school was due to open, Dagmar received a private telegram from the Registrar of the University. The telegram contained just four words: “Congratulations Dagmar. You’ve passed.”

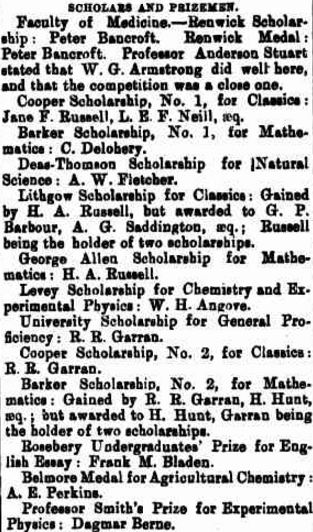

List of Scholars and prizes, with Dagmar Berne (listed at the bottom) being awarded a book for Professor Smith’s Prize for Experimental Physics. Source: The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser Thursday 7 May 1885 page 6

Dagmar’s relative, Dr Vanessa Witton (2008) – who is the great great great great niece of Dagmar’s mother – explains how dedicated Dagmar was to her studies:

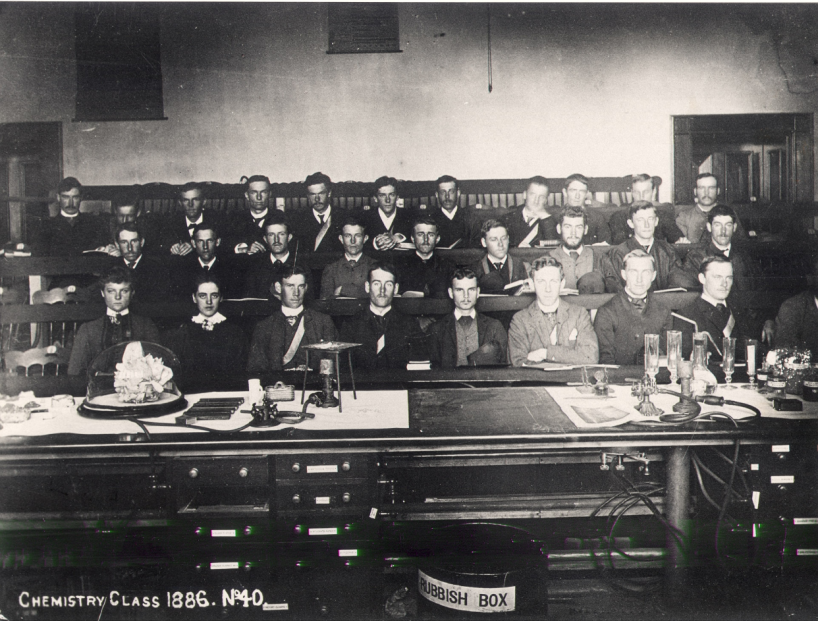

Dagmar entered the University in 1884. She successfully completed her first year studying Latin, French, Euclid, Algebra, Trigonometry, Arithmetic, Chemistry, Physics and English. Although no diaries or letters penned by Dagmar remain, we know from her sister and contemporaries that she was intelligent and deeply dedicated to her studies, and someone who was shy, kind, and disliked shallowness and bigotry. She was also ambitious and determined to take advantage of the opportunities which were becoming increasingly available to women. By 1885, women students were allowed to study medicine at the University, provided they had completed the first year of Arts. Dagmar was the first and only woman to enrol in the third intake of fifteen medical students in 1885.

(page 30)

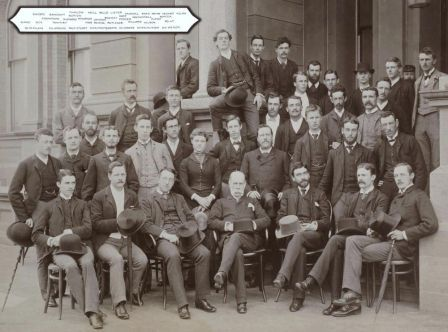

Dagmar led the way for other Australian women to enrol at universities. This photograph from University of Sydney Archives has Dagmar Berne front row on the furthest left. Next to her is Fanny Elizabeth Hunt who transferred from Arts into the Faculty of Science. Miss Hunt would become the first woman to graduate with a Bachelor of Science. Source: University of Sydney Archives accessed at http://sydney.edu.au/arms/archives/history/students_early_women_Hunt.shtml

Among Dagmar’s fellow students were “the first two women to graduate in Arts at Sydney, Misses Mary E. Brown and Isola Thompson” (Neve (1980) page 63. Miss Berne is described by both M.H. Neve and Dr Vanessa Witton as being determined, charming and hating shallowness and bigotry. Neve (1980) mentions that the university student had the support of her mother:

…[Dagmar] was always considerate, always willing to help when help was wanted, kindly to those around her, but at the same time reserved; loyal to her family and adored by her sisters and brother: and her mother was very proud of this independent daughter of hers. She valued Dagmar’s opinion, turning to her in consultation of family affairs, appreciating her clear judgment and general insight. Perhaps it was, seeing so firmly moulded a character in one so young, that this strengthened Mrs Berne’s support of her eldest daughter’s desire to study medicine. Both knew that so unconventional a choice would require not only her own courage and resilience to succeed but also all the help her mother could give her….

(page 63)

It was not only her mother and family who saw admirable qualities in Dagmar. Two of her contemporary students – Dr Cecil Purser and Dr Robert Scot Skirving – saw positive attributes in Miss Berne. Dr Cecil Purser, who would go on from being a physician to be the vice chancellor and deputy-chancellor of the University of Sydney, stated that Dagmar was “a reserved woman, with plenty of intelligence and no small industry”. Dr Scot Skirving described Dagmar as a ‘quiet, friendly sensible girl – and no fool’ (Neve (1980) page 64). Dr Scot Skirving came to the University of Sydney to lecture by one of his fellow students at Edinburgh University, Dr Thomas Anderson Stuart. Sadly the two esteemed academics didn’t share the same views on Dagmar. Witton (2008) states that Dr Anderson Stuart “…publicly voiced his opposition to women in medicine and his belief that they were unsuited to its study.” (page 30). Anderson Stuart had an ally in Vice Chancellor Sir H Normand MacLaurin, with Witton (2008) stating that “MacLaurin claimed that no woman would graduate in medicine while he was Vice Chancellor” (page 30)

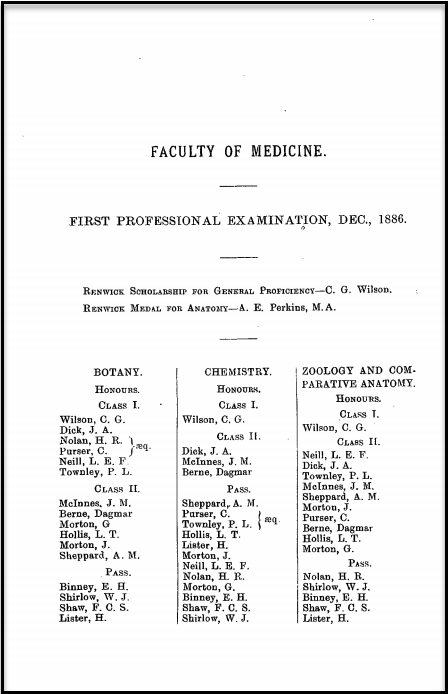

As recorded in The Sydney University Calendar 1887 Dagmar Berne achieved Second Class Honours in Botany, Chemistry and Zoology & Comparative Anatomy. Cecil Purser is also listed. Source: The Sydney University Calendar Archive

This was in contrast to how Neve (1980) describes Dagmar’s fellow medicine students as

…sympathetic and considerate evincing not the slightest objection to having a woman amongst them. One of them years later remarked that, admiring her courage, they always took the greatest care that she should never overhear any loose talk or coarse jokes. They knew her as an industrious and conscientious student, sincerely interested in her work, and they respected her the more.

(page 64)

Third year medical students with sole female Medical student, Dagmar Berne, in the centre. Source: University of Sydney Archives http://sydney.edu.au/arms/archives/history/senate_exhibitions/students_women_history_medicine.shtml

In 1886 Dagmar passed her First Professional Examination, finishing eight out of a class of sixteen. She obtained second class honours in Botany, Chemistry, Zoology and Comparative Anatomy. In Dagmar’s class exams she came fourth in Junior General and Descriptive Anatomy, fifth in Botany and seventh in Chemistry (Moorhead, 2008 page 9) However success did not follow Dagmar into her second year of medicine. Dr Robert Scot Skirving was surprised by Dagmar’s inability to pass the second year subjects. Moorhead (2008) quotes him as saying “I know that Dagmar did quite creditably in the earlier subjects, such as physics, chemistry, botany and zoology and also in junior and practical anatomy. Apparently she somehow got tied up in the subjects of the Second Professional Examination.” (page 9)

One of Dagmar’s relatives, Dr Vanessa Witton (2014) records Miss Berne’s determination to persevere despite unfair discrimination and a hostile learning environment:

Berne failed the First Professional Examinations in her first year of Medicine (II) in 1885, although she had won Professor John Smith’s Prize for Experimental Physics, an annual book prize awarded to the most distinguished student at the Class Examination Viva Voce in Experimental Physics….Berne repeated the year and then passed in 1886. She entered Medicine III in 1887 and Medicine IV the following year but failed the Second Professional Examinations of 1888. She was still studying Medicine IV in 1889 and passed the first two sections of her Second Professional Examinations, but failed Pathology and Materia Medica. She was allowed to take deferred examinations in these subjects in March 1890, but failed again.

Dagmar Berne dated 1890. Source: University of Sydney Archives http://sydney.edu.au/arms/archives/history/senate_exhibitions/students_women_history_medicine.shtml

While Dagmar was still experiencing difficulties with her ongoing health issues and the narrow-mindedness of university superiors, Dr Witton (2014) records that Miss Berne still involved herself in university life. Dagmar was “…elected one of four office bearers of the University’s Ladies Tennis Club and was a member of the University Musical Society.” (Source: http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/berne_dagmar)

It was becoming clear to Dagmar that the male prejudice of the university officials would prevent her from following her dream. De Vries (2001) recalls something the young Miss Berne told her mother: “Mama, I’ve failed again. I know I work hard enough, but sometimes I think it’s just because they don’t want to pass me” (page 97)

Hope on the Horizon

Just as Dagmar was beginning to despair of graduating in Medicine, in 1888 she met Britain’s Dr Elizabeth Garrett Anderson who was lecturing on “Education” for women and girls at the Sydney School of Arts (Witton 2014 http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/berne_dagmar). Dr Garrett Anderson had experienced prejudice in her journey to become the second woman in the world to be registered as a doctor, as described by De Vries (2001):

In 1870 Dr Elizabeth Garrett Anderson (1836-1917) became the second woman in the world to register as a doctor but was refused entry to a British medical school due to her gender. She had the necessary funds to qualify as a doctor in Paris. Having struggled herself she was very sympathetic to the difficulties placed in the path of Australia’s first women medical students like Dagmar Berne and Constance Stone.

Dr Garrett only gained the right to practise medicine in England through legal advice that a loophole in the constitution of the Society of London Apothecaries (who used the word ‘person’ rather than ‘man’ in their admission regulations) could admit her as a doctor. The Society found they could not legally prove that Dr Elizabeth Garrett was not a ‘person’ so was forced to admit her as a practising doctor. (page 92)

Dr Garrett Anderson explained that the solution to Dagmar’s problem was to graduate overseas just like she had done. Having started an all-women hospital, Dr Garrett Anderson could provide her with hospital experience – something else the early female medical students were denied for many years. De Vries (2001) details that Dagmar sailed ten thousand miles to London to continue studying medicine and taking up Dr Garrett Anderson’s offer of a training residency in her hospital (page 98)

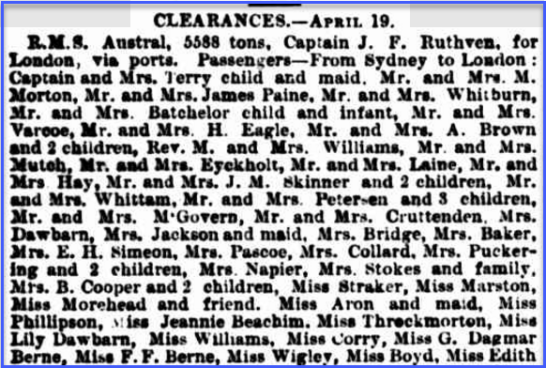

This newspaper article contains the names of Miss G. Dagmar Berne and her sister Miss F.F. Berne, bound for London on board RMS Austral. Source: Sydney Morning Herald Monday 21 April 1890 page 6

Dagmar’s sister, Florence, also wanted to study medicine having tired of running a school. Plans were made for both Berne sisters to move to London. “Both girls had been left a legacy and could afford to live [in London], provided they chose inexpensive lodgings and allowed themselves few luxuries (De Vries 2001 page 98) While supportive of her daughters’ desire to study abroad, Mrs Berne was “…unhappy at the suggestion that her daughters should transfer their entire capital to London. She advised them to take only a portion and leave the balance in Sydney, where it would earn a much better rate of interest. Both girls readily agreed.” (De Vries 2001 page 98).

Dagmar completed her studies at the London School of Medicine for Women (where Dr Garrett Anderson was Dean) and the two girls boarded with an English family in St Pancras (Witton 2014 http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/berne_dagmar) Academically, Dagmar was soaring, with De Vries (2001) stating that “…she passed the Society of Apothecaries’ exams in anatomy and physiology with flying colours.” (page 98) However physically, the damp accommodation and foggy chilly London winters were exasperating Dagmar’s existing health issues. Dr Witton (2014) records that former colleague, Dr Robert Scot Skirving “…unexpectedly met her at York Station during these years, and wrote later that she looked ‘worn and rather frail’, and rose from her bed to attend examinations, despite active pleurisy” (http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/berne_dagmar) While Dagmar’s determination allowed her to pass her exams, her detiorating health was a concern to her and sister Florence.

Yet More Tragedy

While Dagmar’s life seemed an endless experience in heartbreak, prejudice and obstacles, there was more to follow in her last year of training. De Vries (2001) states that Dagmar:

….received a letter from her mother informing her that their Sydney bank had failed in the financial downturn that characterised Australia in the 1890s. The girls’ capital was lost, along with the rest of the Berne family money. Her brother Frederick had to leave school and was looking for work; her younger sister Eugenie was helping support the family by teaching. By this time the money the two sisters had brought to England had nearly run out. This news signalled the end of all their hopes. Florence realised that Dagmar was so near to completing her course that loss of income to support her was a tragedy. There were no government grants, no scholarships available for women to study medicine. (page 99)

De Vries (2001) highlights that while Dagmar was despairing, Florence realised that she had something that Dagmar didn’t possess – teaching experience. In complete secret to her older sister, Florence found a job as a governess and even arranged with the bank to transfer her remaining money to Dagmar’s account (page 99) Having determinedly persisted against male prejudice, Dagmar now found her own sister’s stubbornness one obstacle she couldn’t overcome. De Vries (2001) explains:

Florence countered Dagmar’s ensuing protests by saying that they could not let their mother down. There was only enough money for one of them to qualify as a doctor. It had to be Dagmar, who was now able to continue studying in spite of her weight loss and a persistent cough. (page 99)

Qualification & Vocation

Dr Vanessa Witton (2014) details that following Dagmar’s graduation she

…gained the Licentiate of the Society of Apothecaries (LSA) in London in 1891. She then relocated to Edinburgh. In 1893 she gained the Scottish Triple: The Licentiate of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh (LRCS), the Licentiate of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh (LRCP), and the Licentiate of the Faculty of Physicians and Surgeons of Glasgow (LFPS).

Neve (1980) records that in 1893 Dagmar also collaborated in a medical book with Dr Mary Scharlieb, although no copy of the published book was given to either Dagmar or the Berne family (page 68). Dr Witton (2014) reports that in 1893 Dr Berne was appointed Clinical Assistant at the North Eastern Fever Hospital in Tottenham; before travelling to Ireland to study midwifery at The Rotunda Hospital, Dublin in 1894.

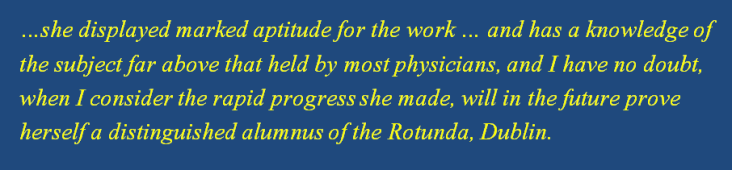

Dagmar’s dedication and passion for her work did not go unnoticed. This quote about Dr Berne is a glowing character reference from the Senior Assessment Master at The Rotunda Hospital, Dublin. Source: Dictionary of Sydney website article by Dr Vanessa Witton (2014) http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/berne_dagmar#page=17&ref=notes

Returning to Australia

While Dagmar had completed her studies and gained invaluable work experience due to moving to England, sadly the climate did nothing for her health. Neve (1980) notes that Not only had the total concentraion on her studies taken great toll of her general health, but the additional worries of lack of finance (and, as her family rightly suspected, inadequate care and insufficient bodily nourishment during those last struggling months), combined with the unsuitability of the damp English climate, had greatly debilitated her. (page 68)

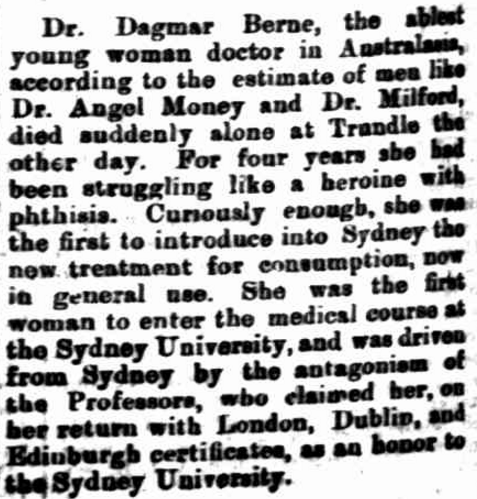

Therefore Dagmar returned to Sydneyin December 1894, gaining registration with the Medical Board of New South Wales on January 9th 1895. Dagmar Berne was only the second woman to be registered after Dr Constance Stone. Dr Vanessa Witton (2014) references a The Singleton Argus report that her Sydney professors “claimed her on her return with London, Dublin and Edinburgh certificates, as an honour to the Sydney University” (http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/berne_dagmar)

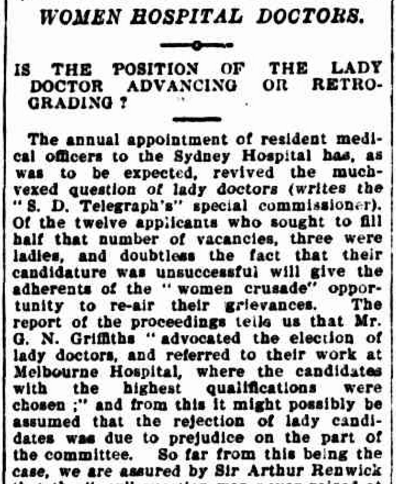

Extract of an article in The Brisbane Courier where Dr Dagmar Berne advocates for Australia following Britain’s lead in establishing “women doctors in women’s hospitals for women patients” Source: The Brisbane Courier Wednesday 5 January 1898 page 2 To view the article in its entirety click here

While the University of Sydney was displaying a more enlightened approach to women doctors, Dagmar still experienced obstructionism from general hospitals who refused to permit her to work on their premises. This included two of Sydney’s major hospitals, Prince Alfred Hospital and Sydney Hospital. Even Dr Berne possessing membership of the New South Wales branch of the British Medical Association had no effect. (Witton 2014 http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/berne_dagmar) In spite of yet another example of unfair treatment, Dagmar continued to share her vision that “…female doctors were needed to care for the medical problems peculiar to women and recognised that their professional development could be advanced by establishing a hospital run by women for women in Sydney.” (Witton, 2014 http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/berne_dagmar)

Denied access to hospitals, Dagmar opened a private practice, earning high fees. However her healthy was deteriorating and being noticed by others. Neve (1980) records that younger sister Eugenie (who became Mrs E.N. Buswell and greatly assisted M.H. Neve when she was writing her book ‘This Mad Folly!’: The History of Australia’s Pioneer Women Doctors) was now living with Dagmar.

Finally Dagmar submitted to the imploring requests of her younger sister Eugenie, who was now her constant companion and who adored this clever sister, and agreed to undergo a medical examination. …her suspicions were confirmed that she had advanced tuberculosis… (page 68)

Her determination and desire was strong, but her pulmonary system was not. However Dr Berne was not one to let her illness stop her following her pursuits. Dr Witton (2014) records that in addition to her private practice, Dagmar also:

- addressed the local branch of the Womanhood Suffrage League at Petersham Town Hall;

- was involved with public meetings in connection with the Kindergarten Union of New South Wales;

- worked with underprivileged women and girls in the lower dock area of Woolloomooloo (for little or no fees);

- delivered food and hygiene lectures to The Working and Factory Girls Club;

- was vice-president, and later president, of the Stanmore Lady Wheelers (a Sydney women’s bicycle club; and

- writing letters to The Sydney Morning Herald advocating women’s health.

http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/berne_dagmar

However stubborn Dagmar was, her family were at least just as stubborn. They finally convinced her to move to a better climate for her own health’s sake. As Dr Vanessa Witton (2014) describes:

By 1898, Berne’s health was failing; she had a persistent cough and her body was wasting…. She relinquished her medical work in Sydney and moved to Springwood, in the Blue Mountains, which had an elevated climate, renowned for its health-giving properties. Florence Berne was also principal of the Springwood Ladies College. Dagmar lived at the college, where the curriculum, rich in physical culture, calisthenics and outdoor games such as golf and tennis, reflected the exhortations of Dagmar Berne and Elizabeth Garrett Anderson that women should lead lives full of physical activity. http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/berne_dagmar

Trundle: A New Home

Although the Blue Mountains climate was better than the Sydney suburb of Newtown, and much better than London, Dr Berne’s health was still deteriorating. De Vries (2001) writes that family friends, the Morrisseys, owned property in Trundle. This property was Yarrabundie Station and in 1900 Dagmar moved further west, hoping that the drier warm climate would aid her recovery attempts.

Initially it is recorded that Dr Berne practised medicine on the Yarrabundie property before taking up professional rooms at Trundle Hotel, then owned by Mrs Honora Moloney. Trundle accepted Dr Dagmar Berne as one of their own, with the district desperately needing a doctor. According to Watts & Wright (1987) Dr Berne was at least Trundle’s second doctor, although speculation remains as to whether the first doctor, Alfred H. Florance, was even a qualified doctor (page 86)

Such was her affection and dedication to her patients, that despite being sick herself, Dr Berne arouse from her sick bed to treat a patient in the Trundle Hotel. Dr Witton (2014) records this day as being 22 August, 1900 while Watts & Wright (1987) record that the patient she treated was one of the McKeowen familiy who had been injured by broken glass, and was in such a weak state that another resident had to support her while she carried out the operation (page 88). This turned out to be her last patient, with Dr Dagmar Berne dying in her room of Trundle Hotel around midnight.

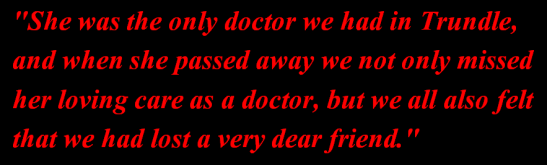

De Vries (2001) records the words of one of her Trundle patients, Mrs Long:

Dr Berne was very frail and sick and was sometimes so weak she could hardly shake a bottle of medicine. She was still very pretty with a neat slim figure. As a doctor she was very conscientious and capable and everyone in Trundle loved and respected her, for she was so kind and took such a great interest in all her pateints, especially the children. She was always very concerned in the treatment of mothers following childbirth, insisting they have plenty of rest … before they began their ordinary domestic work again. She was probably far in advance of her time as far as this was concerned. She believed that far more women doctors were needed as women understood these things far more than any male doctor could.

(page 100)

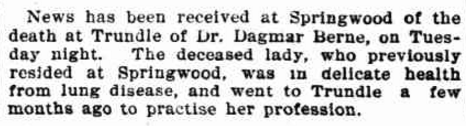

Report of Dr Dagmar Berne’s death. Source: Evening News Friday 24 August 1900 page 2

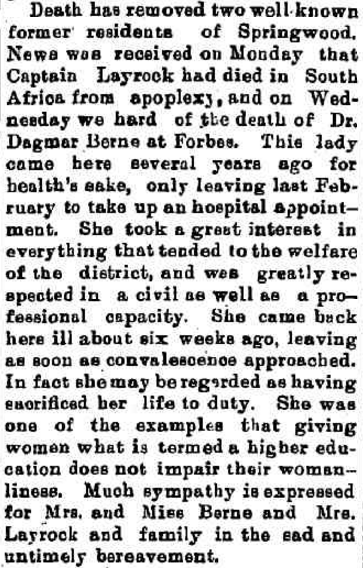

Dagmar’s life helped shatter the myth that women couldn’t and shouldn’t pursue higher education. Source: The Mountaineer Friday 24 August 1900 page 3

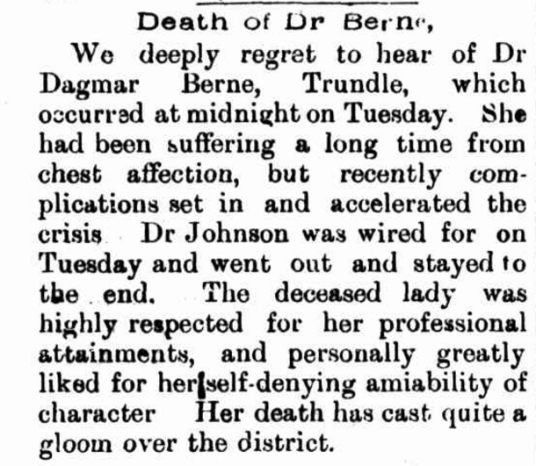

News of Dr Berne’s death ‘has cast quite a gloom over the district’! Source: Western Champion Friday 24 August 1900 page 11

Dr Dagmar Berne’s death caused widespread grief in the Trundle district. This quote, from patient and old Trundle resident Mrs Long, exemplifies this. One of Mrs Long’s daughters, Mary, was so upset upon hearing the news that she cried all day. Source: Neve, M. H. (1980). ‘This Mad Folly!’: The History of Australia’s Pioneer Women Doctors. North Sydney, NSW: Library of Australian History. page 69

Legacy

While Dagmar Berne’s life may have been tragically brief, her legacy is still present today. Dr Milton Lewis (2014), writing in the Medical Journal of Australia believes that Dagmar’s successful enrollment at Sydney University caused the University of Adelaide to open medical enrollment to women (page 57). This resulted in the enrollment and successful graduation of Laura Margaret Hope, herself an Australian medical pioneer. Her graduation in 1891 “…was applauded by the chancellor (Sir) Samuel Way and by women suffragists.” (Jones,H 1996)

Dagmar Berne led the way for many women to pursue university degrees, not just in medicine. Dr Witton (2014) claims that her vision for a women’s hospital “…would not be realised until 1922, when doctors Lucy Gullett and Harriett Biffin established The New Hospital for Women and Children, later the Rachel Forster Hospital.” Robert Moorhead (2008) quotes Dr Robert Scot Skirving as having reported that “…by the pious act of her mother, her memory in the University of Sydney, is perpetuated by the foundation of the Dagmar Berne Scholarship to be awarded to the woman medical graduate who takes the highest marks of her year in the final examination for the MB degree.” (page 16)

Neve (1980) records that although Dagmar:

…was buried in the little cemetery at Trundle, but a few years later Mrs Berne had the body disinterred and removed to Sydney for reburial in the family area of Waverley Cemetery: an action of which the rest of the family disapproved, considering her last resting-place should have remained among the people whom she had so much helped and loved during her brief final years, and who had themselves held her in affection and appreciation.

(page 69)

Dr Witton (2014) states although Dagmar considered herself Anglican, “In 1901, Catholic patients donated a pair of bronze altar vases to the Roman Catholic Church of St Michael’s at Trundle, which are inscribed ‘In Loving Memory of Dagmar Berne, Licentiate Royal College Physicians and Surgeons’. (http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/berne_dagmar) Neve (1980) – who consulted with Trundle local, J.R. Burke of the Trundle and District Development League – relates that these came from a patient whose husband was hotelkeeper at Forbes (page 69).

Dr Witton (2014) records that the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) suburb of MacGregor honours Dr Berne with Berne Place, Berne Crescent and Dagmar Berne Street (Dr Vanessa Witton ACT Planning and Land Authority website, accessed August 12, 2012, http://www.actpla.act.gov.au/home) Refer http://www.planning.act.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0003/896340/Macgregor_Sheet_3_of_3.pdf

Dr Dagmar Berne is today still remembered in Trundle, where she is the Patron Saint of the Trundle Hotel (http://www.trundlehotel.com.au/dagmar.html)

Street sign of Dagmar Berne Street in MacGregor ACT. Source: Google Street View

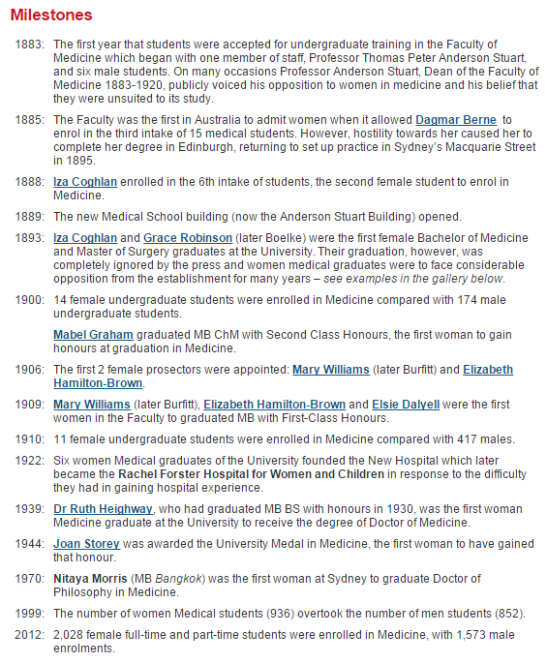

Dagmar’s legacy: The first of the many milestones in Medicine for Australian Women at University of Sydney. Source: University of Sydney Archives accessed at http://sydney.edu.au/arms/archives/history/senate_exhibitions/students_women_history_medicine.shtml

Dr Berne’s appointment created a lot of positivity for the people of Trundle. Source: Western Champion, Friday February 2nd 1900, page 8

Trundle Hotel, where Dr Dagmar Berne passed away after attending a sick patient while she herself was quite unwell. Trundle Hotel has made Dagmar Berne its patron saint. Source: Trundle Hotel website

Despite being told she would never graduate at Sydney University, Dagmar Berne was considered an honour to the educational institution when she returned with certificates from London, Dublin and Edinburgh. Not only did she help inspire other women studying at university (whether undertaking medicine or another discipline) but she introduced new treatments that saved hundreds of lives. Source: The Singleton Argus Saturday September 1 1900 page 4

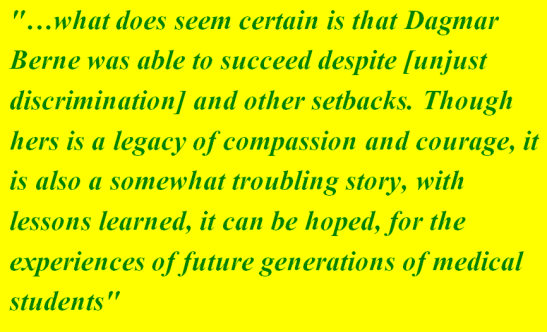

The Last Word. Hopefully lessons are learnt and also that we remember the compassion, courage and integrity of Dr Dagmar Berne. Source: Moorhead, R. (2008). Breaking New Ground: The Story of Dagmar Berne. Health and History, 10(2), 4-22. doi:10.2307/40111301

REFERENCE LIST

- Dr Dagmar Berne [Photograph found in Archives, University of Sydney , Sydney]. (1980). In ‘This Mad Folly!’: The History of Australia’s Pioneer Women Doctors (By Marjorie Hutton Neve, p. 81). North Sydney, NSW: Library of Australian History.

- Neve, M. H. (1980). This mad folly: the history of Australia’s pioneer women doctors. North Sydney, NSW: Library of Australian History.

- MadMonarchist. (1970, January 01). Monarch Profile: Queen Victoria of Great Britain. Retrieved January 11, 2017, from http://madmonarchist.blogspot.com.au/2013/04/monarch-profile-queen-victoria-of-great.html

- Image Princess Beatrice of Battenberg; Queen Victoria by Unknown artist oil on canvas, late 1860s-early 1870s NPG 5828

© National Portrait Gallery, London used under permission of Creative Commons - Witton, V. (2014). Dagmar Berne c1890 [Photograph found in State Records NSW, Dictionary of Sydney, Sydney]. Retrieved December 15, 2016, from http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/berne_dagmar (Originally photographed 2014)

- Moorhead, R. (2008). Breaking New Ground: The Story of Dagmar Berne [Abstract]. Health and History,10(2), 4-22. doi:10.2307/40111301 Retrieved December 17, 2016, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40111301

- Inglis, K. (1952). Centenary of the University of Sydney. British Medical Journal,2(4781), 439-441. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4781.439 referenced in

- Moorhead, R. (2008). Breaking New Ground: The Story of Dagmar Berne Health and History,10(2), 4-22. doi:10.2307/40111301 Retrieved January 17, 2017, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40111301

- Ross, M. (1996). The Royal Medical Society and Medical Women. Proceedings of the Royal College of Physicians Edinburgh,26, 630. doi:10.2307/40111301 referenced in

- Moorhead, R. (2008). Breaking New Ground: The Story of Dagmar Berne Health and History,10(2), 4-22. doi:10.2307/40111301 Retrieved January 17, 2017, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40111301

- Lutzker, E. (1967). Edith Pechey-Phipson, M.d.: Untold Story. Medical History,11(01), 41-45. doi:10.1017/s0025727300011728 referenced in

- Moorhead, R. (2008). Breaking New Ground: The Story of Dagmar Berne Health and History,10(2), 4-22. doi:10.2307/40111301 Retrieved January 17, 2017, from http://www.jstor.org/stable/40111301

- Witton, V. (2014). Dagmar Berne. Retrieved January 4, 2017, from http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/berne_dagmar

- De Vries, S. (2001). Great Australian Women: From Federation to Freedom. Pymble, N.S.W.: HarperCollins.

- Hardie and Gorman Pty Ltd, ‘The Bernefield Estate, St. Peters [cartographic material] : for auction sale on the ground, at 3 o’clock, Saturday 2nd November 1895’, National Library of Australia, MAP Folder 157, LFSP 25, accessed January 20, 2017, http://nla.gov.au/nla.map–lfsp2537

- Google Street View of Berne Street in May 2016, retrieved from https://www.instantstreetview.com/@-33.916113,151.173419,139.1h,1.36p,0.27z January 20th, 2017

- DEATH OF MR. BERNE. (1874, April 2). The Bega Gazette and Eden District or Southern Coast Advertiser (NSW : 1865 – 1899), p. 2. Retrieved January 20, 2017, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article106753937

- The University Commemoration. (1885, May 7). The Maitland Mercury and Hunter River General Advertiser (NSW : 1843 – 1893), p. 6. Retrieved February 2, 2017, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article18884314

- Chemistry Class 1886 [Photograph found in Archives, University of Sydney, Sydney]. (n.d.). Retrieved February 1, 2017, from http://sydney.edu.au/arms/archives/history/students_early_women_Hunt.shtml

- Witton, V. (September 2008). Dagmar Berne’s Story. Radius: The Magazine of the University of Sydney Medical Alumni Association and the Faculty of Medicine,21(3), 30-31. Retrieved December 23, 2016, from http://sydney.edu.au/arms/archives/history/documents/Dagmar.pdf

- ENTERTAINMENT. (1874, September 24). The Bega Gazette and Eden District or Southern Coast Advertiser (NSW : 1865 – 1899), p. 2. Retrieved January 20, 2017, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article106754814

- Helen Jones, ‘Hope, Laura Margaret (1868–1952)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, http://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/hope-laura-margaret-10541/text18717, published first in hardcopy 1996, accessed online 1 February 2017

- University of Sydney. (1887). The Sydney University Calendar 1887 (University of Sydney Calendar Archive 1887, Publication). Retrieved February 2, 2017, from http://calendararchive.usyd.edu.au/Calendar/1887/1887.pdf Referenced by Dr Vanessa Witton on http://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/berne_dagmar

- Third year medical students [Photograph found in Archives, University of Sydney, Sydney]. (2013). Retrieved February 2, 2017, from http://sydney.edu.au/arms/archives/history/senate_exhibitions/students_women_history_medicine.shtml (Originally photographed 1887)

- Dagmar Berne [Photograph found in Archives, University of Sydney, Sydney]. (2013). Retrieved February 2, 2017, from http://sydney.edu.au/arms/archives/history/senate_exhibitions/students_women_history_medicine.shtml (Originally photographed 1890)

- CLEARANCES.—APRIL 19. (1890, April 21). The Sydney Morning Herald (NSW : 1842 – 1954), p. 6. Retrieved February 3, 2017, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article13767488

- (1900, September 1). Singleton Argus (NSW : 1880 – 1954) , p. 4. Retrieved February 3, 2017, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-page7878040

- WOMEN HOSPITAL DOCTORS. (1898, January 5). The Brisbane Courier (Qld. : 1864 – 1933), p. 2. Retrieved February 3, 2017, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article3664112

- Watts, J. P., & Wright, C. F. (1987). The Story of Trundle: A Country Town and Its People. Trundle, N.S.W.: I. Berry and J. Curr.

- Advertising (1900, August 24). Evening News (Sydney, NSW : 1869 – 1931), p. 2. Retrieved February 3, 2017, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article112589215

- Springwood. (1900, August 24). The Mountaineer (Katoomba, NSW : 1894 – 1908), p. 3. Retrieved February 3, 2017, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article194840414

- Death of Dr Berne. (1900, August 24). Western Champion (Parkes, NSW : 1898 – 1934), p. 11. Retrieved February 3, 2017, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article112286116

- Lewis, M. J. (2014). Medicine in colonial Australia, 1788-1900. The Medical Journal of Australia,201(1), 5-10. doi:10.5694/mja14.00153 Retrieved February 3, 2017, from https://www.mja.com.au/system/files/issues/201_01/lew00153.pdf

- Patron Saint of the Trundle Hotel. (n.d.). Retrieved December 17, 2016, from http://www.trundlehotel.com.au/dagmar.html

- Google Street View of Dagmar Berne Street, MacGregor ACT in December 2009, retrieved from https://www.instantstreetview.com/@-35.214863,149.002392,-37.53h,6p,1.13z

- Brief Mention. (1900, February 2). Western Champion (Parkes, NSW : 1898 – 1934), p. 8. Retrieved August 27, 2018, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article112284042

- Bergmann, L. (2013). Early Women Students. Retrieved February 02, 2017, from http://sydney.edu.au/arms/archives/history/senate_exhibitions/students_women_history_medicine.shtml

- Photograph of Trundle Hotel – Dr Dagmar Berne. (n.d.). Retrieved January 17, 2017, from http://www.trundlehotel.com.au/dagmar.html

- CURRENT NEWS. (1900, September 1). Singleton Argus (NSW : 1880 – 1954) , p. 4. Retrieved February 3, 2017, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article78891689

This is a very interesting read. An amazing story about an amazing woman

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Eileen, she was indeed an amazing woman full of courage, resilience and determination. Thanks for your feedback

LikeLike

What an amazing story. It is a wonder that we don’t know more about pioneering women like this. It makes you think about what she could have achieved had she been born 100 years later and her tuberculosis treated.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for your comments, Lucy. Dr Dagmar Berne is an inspiration to everyone, and we all need to acknowledge the sacrifice, determination and injustice that other people suffered.

LikeLike

It’s nice to read about my great aunt Dr Dagmar Berne

LikeLike

Hi Dr George John Berne,

Thank you for taking the time to read and comment on Parkes Library’s history blog. Your great aunt was a remarkable woman and one who older people in Trundle still talk about fondly. If you have any additional information (stories, photographs etc) that you are willing to share to make this blog post more interesting, please contact me dan.fredericks@parkes.nsw.gov.au Kind regards.

LikeLike